Shells with a Second Life

01 Sep 2025

Ghost Fleet Oyster Company’s mission to feed the coast, rebuild reefs, and protect North Carolina’s waters

By Jade Neptune

At Ghost Fleet Oyster Company, the flavor of their oysters speaks for themselves. There’s a word for it, merroir, derived from the French word “mer,” meaning sea. For environmentalists and food connoisseurs alike, this refers to the way local waters infuse the taste of one of the most iconic dishes in Coastal Carolina. For Cody, owner and captain of Ghost Fleet, they taste like home.

Cody, a former fireman, and his wife Rachel founded Ghost Fleet together nearly five years ago. As they put it, “An environmental scientist and a fisherman walk into an oyster bar...and the rest is history.”

Cleaning up Local Waters

“We're both native to North Carolina,” says Cody. “We founded Ghost Fleet off this sustainability platform, oysters being one of the most sustainable styles of farming in the world due to

no inputs.”

The logistics of the farming itself are minimally invasive to the environment, with boat motors being the primary, but necessary, threat to the process. The sustainability doesn’t stop there, though. The oysters themselves give back to the environment in quiet, vital ways.

Cody and Rachel had a simple goal: cleaning up local waters.

“We grow the Topsail Jewel, which is our flagship oyster,” says Cody. “It’s how we connect with a lot of people and is the bread and butter of how we fund the business.”

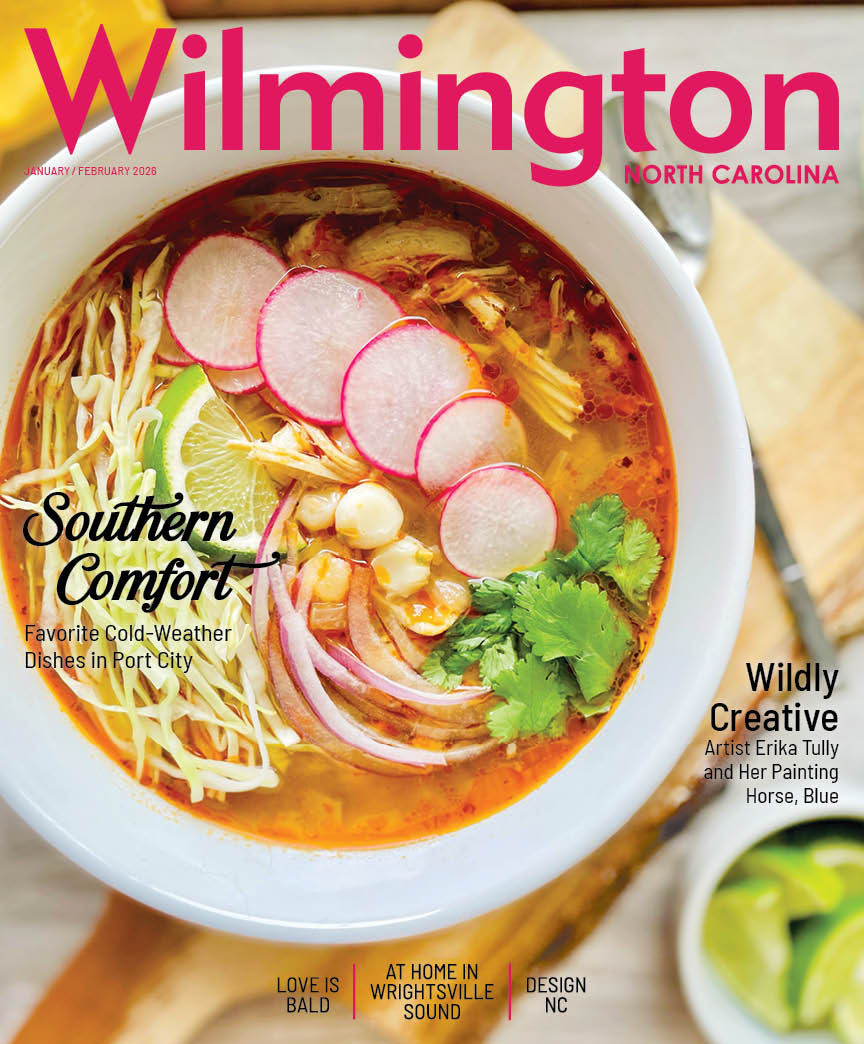

The Topsail Jewel embodies the definition of merroir, referring to the unique influence of an oyster's habitat on its flavor profile. Grown off the coast of Topsail Island, these oysters are known for its slight sweetness and high salinity. This creates a full flavor palette that could belong nowhere but the home where they are grown.

“It’s just a clean, crisp, refreshing oyster that showcases that local Topsail water,” says Cody.

Although an enjoyable perk of the trade, it’s not just the taste that makes them so important to the community. Cody follows the four Fs of oyster farming: They’re friendly for the environment, they create fish habitat, they filter water, and they’re food for people.

At Ghost Fleet Farms, Cody and Rachel farm over one million oysters each year. Adult oysters filter about 50 gallons of water per day.

“That would be 50 million gallons of water filtered just by my oyster farm,” says Cody. “But in the grand scheme of natural oysters, that’s a tiny drop in the bucket. If you can create a reef that has millions and millions of oysters on it, you’re talking about massive ecosystem services and benefits. That’s how we’re going to change the world.”

But after farming them, where do the shells go? For Cody, he knows that he’s not going to make a change on ten oyster shelves, he says. But he does believe they’re going to make a change from ten people’s habits through initiatives like their oyster shell recycling program.

Oyster Shell Recycling Program

Throughout his career as an avid fisherman and oyster farmer, Cody has learned to ask an important question. Who owns the water in the state of North Carolina?

“Any public body of water, most water in the state other than private lakes, from the mountains to the coast, is owned by every citizen,” says Cody. “So, if you live in Asheville, your impact on coastal North Carolina Waters is much bigger than you think.”

Part of how North Carolinians across the state can protect and preserve local waters is by eating sustainable seafood, such as oysters, and supporting ethical farming practices.

“Most people love eating oysters. When I say most people, I’m talking a lot more than you would expect in some capacity,” says Cody. “We can enjoy them in a variety of ways, like Rockefeller or raw, or going to a party where you’re steaming them. But no one has any ideas about where those oysters typically come from, and they have no idea about what you should do with those shells after.”

One primary use for recycled oyster shells is placing them back in the water as a home for other living organisms. Oysters are broadcast spawners, meaning that their fertilized eggs create small larvae like plankton. When the plankton are looking for shelter, their ideal home is on a piece of an oyster shell.

Ghost Fleet Farms partners with organizations across the country that clean the shells, sterilize them using the sun, and return them to the water. Once returned, larva can make its home there.

This process creates what the environmental community knows as artificial reefs, projects that help take the pressure off the wild to recreate reef sanctuaries.

“They’re rebuilding reefs that you can’t harvest off of,” he says. “These are reefs that are going to be there for a long time. The goal there with putting the oyster shell back is that we try to get as many oysters set as possible. When you do, you create these great reefs that can replenish themselves over time.”

With the help of sustainable oyster farms, you can eat oysters 365 days per year while supporting programs that put these crucial organisms back into the water.

Oysters naturally sequester harmful toxins and threats from the water. Overharvesting has led to a severe decline in finding these oysters in their natural environment, but companies like Ghost Fleet are helping to put them back where they belong.

Oyster Farm Tours and Education

Cody isn’t the only one asking questions – he wants you to ask them, too.

“If you have an oyster roast or you're at a restaurant that sells oysters, you just ask the question,” he says. “Just say, ‘Hey, what are you guys doing with your oyster shells?’”

Curiosity is crucial to furthering the cause of sustainable and ethical farming. UNCW also now has a breeding program in addition to several educational programs offered by the UNCW Shellfish Hatchery and Center for Marine Science.

When Cody was growing up, some oyster shells were used to build roads and other larger-scale projects. Today, their purpose varies to include arts and crafts projects, artificial reefs, construction, coastline rehabilitation, and more.

The field is still expanding, and the science is still new for oyster farmers. Even as the industry continues to grow, its strong current of passion keeps it afloat.

“It’s going to get better and better. We are all just trying to live out a patient and a dream as oyster enthusiasts,” says Cody. “We truly love it. It’s the easiest way to go to work when you love. I hope that’s how you all feel about your job.”