The Evolution of Cucalorus

03 Mar 2018

Aesthete Dan Brawley is keeping Wilmington on the map as a creative Center

By TERESA A. McLAMB

“It’s a bit of a joke,” Dan Brawley says, but, it’s also pretty close to the truth that he came to his current position with Cucalorus Festival when he answered the phone in his 2nd year as a volunteer. “They asked who was in charge. I looked around, and I was the only one in the office, so I said ‘I am.’” That was the festival’s 4th year. 2018 marks its 24th.

Along with a dedicated team of volunteers and staffers, Cucalorus has helped put Wilmington on the map, not just as the home of great films and filmmakers, but also as a creative center.

The festival was founded by a handful of people who called themselves Twinkle Doon. Brawley explains, “They were an underground group who were the coolest kids in the local industry, working at Screen Gems and also doing their own work. The first festival, in 1994, screened a few movies downtown.” Two major festivals, South by Southwest and LA Film Festival, were founded the following year. “There were fewer than 100 film festivals in North America then,” he said. Today there are about 3,000.

Cucalorus has grown to 365 events, expanding far beyond film, now to the stage, technology, entrepreneurship and dance. It has undergone rebranding to reflect those changes. More than 20,000 people attended last year’s festival. The festival is making its mark on the local economy. The last economic impact study was completed over ten years ago. It showed a $5.5 million push with a much smaller festival. “We should do another one,” Brawley said with a grin.

The evolution of Cucalorus “has in many cases been a response to things happening in the community. By adding the new facets, we’re responding and adapting. We want to showcase the best our community has to offer. In doing so, we take the best local and international ingredients, put them together, and the outcome will, hopefully, shape the cultural and economic vision of the city,” says Brawley.

Wilmington’s dedication to the arts is visible in pedestrian and studio art, the success and popularity of the Wilson Center, Thalian Hall, and Kenan Auditorium. “We have 32 theater companies,” Brawley said. “That’s unbelievable for a small city. When we did an assessment, we felt there was a wealth of talent and resources around the stage, including comedy.” Cucalorus honors this in many ways including the introduction of films by artists performing original work.

Brawley gives Apple as an example of why Cucalorus works. “Apple has been successful because it stands at the intersection of technology and creativity,” he said. “They’re incredibly well designed. There’s a power of being at the intersection of technology and the arts. It is a valuable magic.”

Brawley went on to say, “21st century technology requires businesses to have a finger in the creative pot, so to speak. No matter what you sell, you need a video. That’s part of the magic of the festival. Wilmington is obviously very well suited to take advantage of those intangible assets. There are very few places that can compete with Wilmington in natural assets. It’s a pretty special place, and now that people can work anywhere [remotely], Wilmington has an incredible advantage over cities with more resources because we’re all working in the cloud. Wilmington is a pretty cool place to sit.”

Cucalorus seems like a long stretch from Brawley’s childhood, building forts with neighborhood kids in the woods just off Oleander Drive and playing golf at Cape Fear Country Club. Sometimes they’d play 36 holes in a day. “The staff took care of us like family,” he said. By the time he was eight, he was competing in tournaments. By 13, he was making his own travel arrangements for tournaments in other states. “A lot of parents would go. I had friends in Clinton who were very talented, and my parents would coordinate with their parents to figure out who was keeping an eye on us.”

As a teenager, he spent summers in Pinehurst, playing the course when it was closed. On one of those afternoons, he serendipitously played several holes with Michael Jordan. Today, he plays about once a year with his dad. “It’s sort of meditative; spending four or five hours outdoors,” Brawley says.

His interests also leaned toward the arts, so while playing golf at Duke, he studied art and art history. Despite his family’s tight bonds with UNC Chapel Hill (alums include both parents, seven uncles, and grandparents), Brawley sided with his maternal grandmother, promising her when he was five that he would attend her alma mater, where she was in the first Duke Chapel Choir.

Returning to Wilmington after graduation, Brawley worked in the film industry, welding on the set of Muppet movies. “I think that’s what hooked me on staying in Wilmington. Growing up, being in Wilmington [long term] wasn’t part of my vision.” Yet, Wilmington’s film industry was at its peak in the 90s when he and many other artists flocked here. “You want to talk about a dream come true for a young artist, living in a city where films were being made. Big budget films employ many people; any kind of visual artist was there on the Muppet movies.” Wilmington had work to offer “without the congestion and other issues of LA and twenty-five people competing for every job,” he noted.

“I was happy and fell backwards into Cucalorus.” Along with film work, he had jobs at a coffee shop, St. John’s Art Museum, and a clothing store. He also volunteered with Cucalorus where he became director in its fifth year.

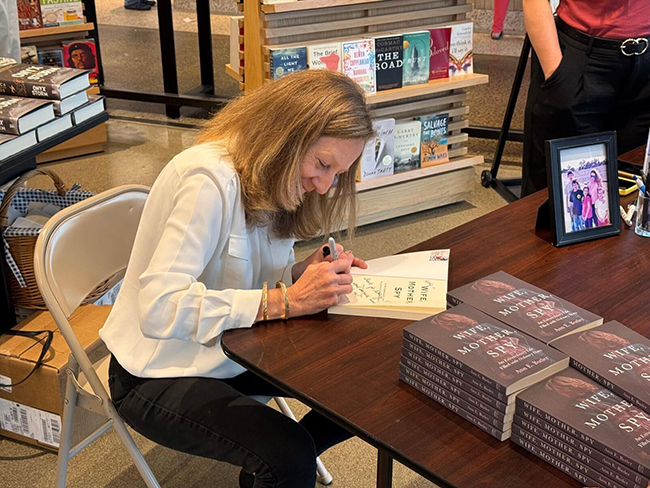

Today, he travels extensively, attending film festivals around the world, and representing Wilmington’s creative community. He is currently president of Film Festival Alliance. Cucalorus is also the driving force behind Lumbee Festival, Tar Heel Shorties, and Surf-a-lorus.

“We are constantly experimenting with the nonprofit model. We think of ourselves as a powerful economic engine.” In his travels, he almost always encounters filmmakers who have either participated in Cucalorus or have heard of it.

He also has a growing cadre of volunteers and trainees. “One of the most important things we do is to provide hands-on learning opportunities for up to thirty-five paid seasonal staff members. We call it our training institution. They’re mostly young graduates who want to learn the industry and spend from one to three years with the festival. Many have gone on to work with other film festivals, Netflix and similar opportunities,” he said.

Cucalorus also has a residency program which brings artists from around the world to Wilmington for three weeks. “We hike Sugarloaf, give them a surfing lesson at Wrightsville Beach, and through the process, the characteristics of the region become infused in their new work.”

Submissions are open and business sponsorships are being sought for the 2018 festival, which runs November 7 – 11.