The Future is Blue

04 Mar 2024

Plastic Ocean Project aims to study and reduce the waste building up in the sea, local river basins, and watersheds

By Carin Hall

“If we fail to take care of the ocean, nothing else matters,” Dr. Sylvia Earle says in the 2014 documentary Mission Blue.

As one of the scientific community's greats, Earle (88) is a world-renowned marine biologist who holds the record for the deepest walk on the sea floor, was the first woman to lead the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and is a fierce advocate for ocean conservation and education.

Inspired in part by Earle, as well as her own experience observing plastic pollution across nearly 10,000 nautical miles that included four of the five global ocean gyres, Bonnie Monteleone co-founded the Plastic Ocean Project in Wilmington to continue the fight against the plight of our oceans. As it turned out, it was the perfect place to do it.

Journey to Wilmington

With an education in journalism and art, Monteleone later discovered the impressive science community at UNCW, where she completed a graduate program in Scientific Writing.

“That's when I learned about plastic in the ocean—and it just got under my craw,” Monteleone says.

Collaborating with the University's scientists, she worked on a thesis to study plastics in the ocean alongside Algalita, a marine research foundation based in California that had been studying plastics in the North Atlantic.

“Oddly enough, a year later, I found myself on the very boat I read about as a student, flying to Hawaii, getting on a 50-foot catamaran and spending 30 days at sea alongside a scientist,” she says. “I conducted surface sampling and saw with my own eyes just how serious this problem is—plastics are in some of the most remote places on the planet.”

Not a single sample collected was absent of plastic. At that point, Monteleone knew she had to do more than just defend her thesis. She reached out to other nonprofits concerned with preserving the ocean but mostly found that they were not yet focused on the same research or were not able to establish a new chapter on the East Coast. Surrounded by a strong community of marine biologists and scientists and living alongside the largest estuarine system on the eastern seaboard, it became clear that she had to start a nonprofit in the Cape Fear region.

“The severity of the issue was so pronounced that I had to do it,” she says. “Plus, we're taking a very different approach. We might be the only nonprofit with the instrumentation to do the level of research necessary to understand just how bad this plastic issue is.”

Inspiring hope

As a board member at the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, Monteleone spearheaded an effort to put Hatteras in the Outer Banks on the map as an official Hope Spot, recognized by the nonprofit Mission Blue under Dr. Earle for its ecological, economic, and historic importance. As one of 11 places selected out of over 200 applicants, Hope Spot Hatteras earned its distinction in 2016—an honor North Carolinians can take great pride in.

In addition to the habitat it provides for important fish species, sea turtle nesting, and over half of the known cetacean species in the world, it's also an important calving area for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whales.

“There may be as many as a third of all the right whales in the world found off our coast,” Monteleone says. “Hatteras has incredible biodiversity, and it behooves us to protect it because it's so important to our economy and the health of our oceans.”

356

As part of the Plastic Ocean Project's many efforts to spread awareness comes a short film, 356, that follows its team on an unexpected journey. Setting out on the water without knowing what the “hook” of the film would be, it, unfortunately, arrived when a baby right whale had been washed ashore nearby, #356 of the 360 expected to be left of its species.

With an alarming uptick in marine mammal deaths in recent years, the goal of the film is to explore the possible causes and solutions. But the message is more empowering than doom-laden.

“I want people to know exactly what they can do,” Monteleone says. “If we can save the North Atlantic right whale, we're certainly going to have a leg up on saving other species in the ocean.”

356 serves as a short film and trailer for a full-length documentary, If the Ocean Could Talk – A Voice for the North Atlantic, expected to come out in the next year, featuring Dr. Earle as the film showcases Hope Spot Hatteras.

Passing the torch

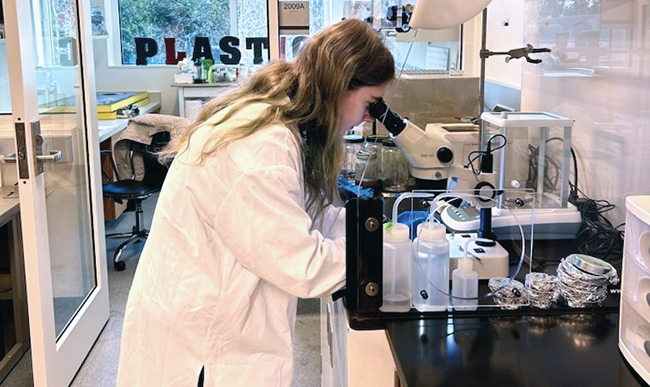

Monteleone teaches a course on Plastic Marine Debris Field Studies at UNCW and manages a lab working with student Directed Independent Studies research, collaborating on projects ranging from fieldwork collecting beach samples to lab analysis looking at plastic leachates, persistent organic pollutants (POPs) uptakes, and plastic ingestion by marine organisms.

For students looking for meaningful careers and job stability, Monteleone hopes to encourage more young people to get involved.

“My vision is that I will hand this on to them to continue doing [Plastic Ocean Project's] work,” she says. “The future looks bright for anyone that cares about the environment. More corporations are having to operate more sustainability, driven by the demands of the public as they become more aware.”

Examples of their work include recently published research analyzing microplastics found across large river basins in North Carolina in partnership with NC State University, UNCW, and Sound Rivers, Inc.

“We helped with the smoking ban on Wrightsville Beach and have data that support it's had a positive impact,” says Monteleone, referencing that cigarettes are the most common litter found on the beach.

Their team is also studying how to make improvements in human and ecosystem health through microplastic reduction found in freshwater, testing samples from watersheds throughout the state.

Lab for hire

Plastic Ocean Project has the unique capability to independently test samples for individuals, businesses, universities, or other nonprofits. One example Monteleone points to is an individual from Florida who wanted to test the pine straw used at a nearby development. After confirming that the material was made of polypropylene, they were able to alert the HOA and the company behind the product of its potential harm during hurricanes that wipe the materials into the ocean.

They've also tested bottles that claim to be BPA-free, many of which are found to either have BPA or contain other toxic chemicals.

Storytelling

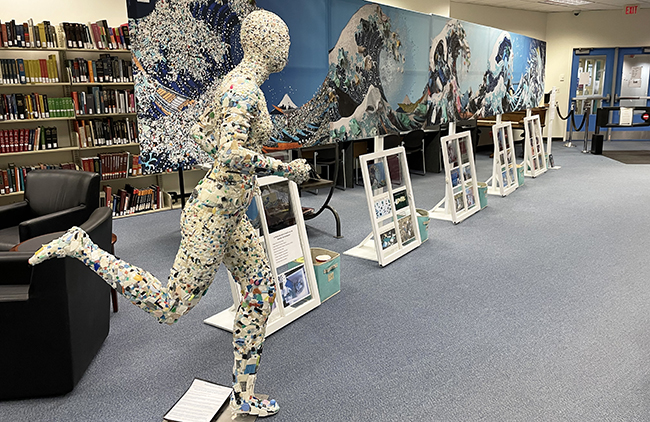

An unusual but effective approach to raising awareness, Monteleone employs her art background, taking her traveling art exhibit around the country featuring a 25-foot canvas that represents each of the five ocean gyres. It’s entitled “What Goes AroundComes Around,” because she says, “The plastics that we're finding out in the middle of the ocean that are breaking up into small fragments are ending up in our fish that we eat and they're also washing back up on our beaches.”

Of some of the plastic she's retrieved from her expeditions, she’s used to create large sculptures like a giant wave. Beautiful as it may be, it’s an ugly reminder of our reliance on single-use plastics. It's also a way to reach more people and new venues, encouraging a discussion around small behavioral changes that can have a significant impact like bringing your own cups to coffee shops, using your own bottles for cold fluids, and bringing your own bags to grocery stores.

Get fancy

Want to do more? Plastic Ocean Project hosts local volunteer events and has its third annual “For the Ocean Gala” coming up this May (tickets available on their website).

“We try to incorporate some fun with the heaviness of the work we do,” says Monteleone.

The “coastal cocktail” attire encourages attendees to show off their best threads in the colors of the ocean. There will be both a live and silent auction, music, and storytelling as the organization celebrates some of its successes from 2023.

“We should be proud,” she says. “This nonprofit grew right here in Wilmington because the locals believed in us and understood that this is important work. So, it's a great way to celebrate those that have brought us into existence.”