The Stories David Joy Was Meant to Tell

01 Sep 2025

A renowned Southern author discusses writing, sobriety, and the necessity of speaking up in difficult times

By Marianne Leek » Photos by Kathryn Smith

David Joy once told my students, “Life's too short for shitty books.” I discovered his work in a Colorado bookstore where he was a staff pick. Early in his career, he regularly spoke with my high school students about books, the outdoors, fishing, and other things that mattered. Widely regarded for his kindness and unpretentious demeanor, Joy is one of the finest Southern writers of his generation.

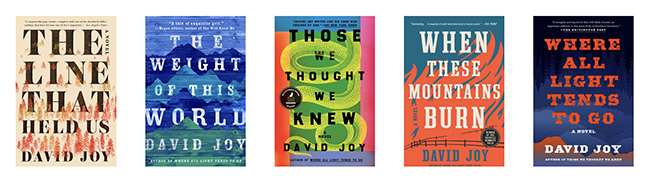

A master at lyrically creating a sense of place, Joy's first three tautly paced novels are rooted in the kudzu-covered mountains of western North Carolina. Each has deeply flawed characters and explores themes of complicated family dynamics, poverty, depression, and addiction. However, his last two novels mark a shift in his writing: “When These Mountains Burn” addresses the growing opioid crisis in western North Carolina, and “Those We Thought We Knew” examines systemic racism and conflicts over the Confederate monuments while shedding light on the removal and relocation of an AME church and its cemetery to make way for a Western Carolina University dormitory.

While Joy acknowledges this shift from simply telling a good story to tackling complex social messages, he says it was less intent that inspired him than an instinctive responsibility to bear witness. “I was living just over the county line into Haywood at the time, and I'd go to the post office to check the mail, and the parking lot would be covered in syringes,” he says. “I'd drive through town and see medics pulling bodies out from under bridges or out of gas station bathrooms where people had overdosed. Addicts were knocking on my front door and asking for sewing needles to skin pop.”

Showcasing some of Joy's finest writing, “Those We Thought We Knew,” published in 2023, is part small-town murder mystery, part lyric poetry, that forces the reader to take a hard look at regional and oftentimes generational familial beliefs regarding racism, heritage, and hate. Joy explains that it took over a decade to write, writing four novels “while I was trying to wrap my head around this story. In a lot of ways, it feels like the book I was put on this planet to write. The heart of that novel is constructed of questions I wrestled with for most of my childhood and conversations that I wish had been had.”

It is not only a work of Southern crime fiction with a powerful social message; at its heart, it is also a profound love story about a deeply connected grandmother and granddaughter, the poetic final chapter circling back to the two dancing and singing in their summer garden to the music of Western North Carolina native, Nina Simone. It may be one of the most beautifully written endings in modern American literature, one that transcends genre.

Protagonist Toya's grandmother is deeply immersed in her rural community and church. Toya's clandestine and provocative art installation elevates the Black church as a primary character. Joy explains: “There are a lot of subtle things happening in this novel, particularly regarding the role of the Black church. The book begins with the true story of a congregation founded by eleven formerly enslaved individuals whose church was forcibly relocated to make way for a dormitory on Western Carolina University's campus.”

Joy recognizes Black churches as community centers, particularly in rural places. “There's a moment in the novel when Toya describes the pain of removal: 'That building had to have been the center of their universe. That church must've felt like gravity.' I think that's true, Joy says. ”I think that oftentimes these churches become the hubs that hold everything together.

“There's also this idea of the Black church as a place of resistance,” he continues. “You think about the way that these buildings were used as spaces to organize during the Civil Rights movement. You think about the words King wrote in 'Letter from Birmingham Jail.' John Lewis talked about this, about this connection between the church and Civil Rights, when he said, 'Slavery was our Egypt, segregation was our Egypt, discrimination was our Egypt,' and so during the height of the civil rights movement it was not unusual for people to be singing, 'Go down Moses way on down in Egypt land and tell Pharaoh to let my people go.' The church plays a really interesting role in that regard, and so there was just no way to tell this story without incorporating some of that reality.”

Swing the Ax

To use two Joy-isms, “Those We Thought We Knew” has recently “grown legs,” encouraging more people to “swing the ax,” speak out against racism, and advocate for others. Joy insists meaningful change can happen within the ebb and flow of our daily lives. “I remember having a reading once, and a white woman stood up and said, 'But what if [speaking up] gets you killed?' I was taken aback,” he explains. “It strikes me as an immense privilege to have that choice, particularly when talking about the protection of those who don't have a choice, who live in perpetual danger of very real violence. [But] what I told her was that the conversations do not have to be these big, public displays. … The majority of these conversations need to be had at the dinner table, on car rides, on front porches, sitting next to people close to us.”

“White people in this country have a serious reluctance, and often outright refusal, to be made uncomfortable,” Joy says. “Quite simply, we are not having these conversations, and even when forced, it is not for any meaningful period of time. That is a matter of privilege. We don't have those conversations because we do not have to have them. Nothing noticeable changes for us by not engaging. Our lives remain the same. I hear these ideas of 'shame' or 'white guilt' tossed around often as this sort of ridiculous side-stepping. It's a convenient way to avoid being made uncomfortable or having to engage in conversations about injustice. I am the direct descendant of enslavers. My family lines on both sides are filled with men who fought to preserve that institution. But I do not feel shameful about that. I do not feel guilty. What I would feel shameful about and guilty for would be recognizing that 160 years later, I still sit as a direct beneficiary of that institution, and keeping my mouth shut. That would be shameful.”

This past spring, a video of him speaking in a way he describes as “on the fly and from the heart” at a Jackson County Commissioners meeting went viral on social media. “I didn't realize that any of that was being recorded, so when it started appearing on social media, I was really surprised,” he says. “It wound up reaching millions of people, and that's pretty shocking to think that something I said in that room at the Justice Center in Sylva echoed that loudly.”

In the video, he addressed commissioners and criticized the removal of two plaques from a Confederate monument that had originally been installed in 2021 to cover up the Confederate flag and an inscription that read, “Our Heroes of the Confederacy.” His words resonated with viewers and those who follow him on social media.

“There was a woman who stood up after me who said some things that I felt were really important, and I wish that those comments had gotten the same attention,” Joy adds. “She pointed out that there were 218 people enslaved [in Jackson County] at the time of the last census, leading into the Civil War. So, setting aside the Jim Crow context of how that statue wound up in front of the Jackson County courthouse, those commissioners are fighting tooth and nail for a statue that memorializes 164 soldiers from Jackson County while telling every descendant of those 218 that they revere the time their ancestors were in bondage. She also read the names of every enslaver in Jackson County, a list that included the surnames of every county commissioner but one. I thought that was incredibly powerful. All of that to say, there are lots of people swinging the ax, and for the most part, it is an act that goes unnoticed.”

The Right Books at the Right Time

Joy grew up in Moore's Chapel, a rural community that has since been swallowed up by the inevitable expansion of Charlotte. He moved to Cullowhee to attend Western Carolina University, and following graduation, he put down roots in Jackson County. Much has been made of the fact that Joy was not only a student in Ron Rash's fiction writing course, but also that the two have become great friends, bonding over their shared love of language and fishing. Joy credits Ron with introducing him to the “right books at the right time,” inevitably steering the early trajectory of his writing career.

“I was never a big reader as a kid, and looking back, it was because I just never got my hands on the right things,” Joy explains. “I'll never forget him giving me a copy of William Gay's 'I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down.' That was the first time I'd ever heard my people and seen places I knew on the page. Until then, I didn't realize you could tell those types of stories. That was a pivotal moment for me as a writer.”

Joy's next novel, “Del Rio,” is stylistically similar to his early writing. “It's dark and gritty and fast, more character study than social critique,” Joy says. “I think these last two novels were trying to do some really big things, and I think I felt really disappointed at the reception… When you try to take risks and do these bigger things, and you watch it go unnoticed, it takes a toll. This novel is an attempt to reclaim that joy for myself… I wanted to write a love story. I wanted to turn the idea of the happy ending on its head. It's a book that's playful with form and voice.”

Joy also shared that he has been working on a spinoff of PBS's award-winning “Southern Storytellers” TV show. He and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown interview writers, artists, and musicians outside the South. Joy mentioned that they had recently interviewed five-time Grammy winner Samara Joy in New York City, as well as novelist S.A. Cosby.

Over the past decade, Joy's readership has grown exponentially, with thousands of new readers discovering Joy, partly due to his recent remarks at the Jackson County commissioners' meeting. He is grateful for new readers and those who have been with him since the publication of his first novel. He also hopes for recognition of the evolution of his craft.

“When I think about the writers, artists, musicians that I appreciate most, growth, evolution, expansion, those are the things I value in their work,” he says. “I want to watch the body of work open like a firework. I want the lens to widen, even if it's a tightening down of the lens, a tightening down of focus, I want the show to get bigger. I want there to be a noticeable honing of craft. I want the levers to be less visible, for things to feel more fluid. The magic trick should never feel like an illusion. It should never feel like a trick. So, all of the things that I want from the artists I admire, that's what I hope the people who are following me feel like they're getting from my work. I hope that's what they feel like they're witnessing.”

I asked Joy to discuss his overall body of work and which novel he's most proud of. “There are things I love about all of them,” he says. “'Where All Light Tends to Go' was the first novel I ever wrote, and there's something magical about that. Those first three novels are sort of grouped to me stylistically, and I think 'The Line That Held Us' was really me at my best within that early style. These last two novels have been social in ways that those first three weren't, and I'm proud of the work those books are trying to do. 'Those We Thought We Knew' just took so long and was such a hard story to get right. It was assuredly the most challenging.”

Finding Peace

Earlier this year on Instagram, Joy candidly discussed his battle with depression and his decision to get sober. “I think it started with just a recognition that there were a lot of really big decisions that needed to be made and knowing that I did not wish to ever look back and wonder if those decisions had been made through a fog,” he says. “I wish I could say there's been some transformational moment, but there hasn't. I'm still trying to juggle a whole lot of things with hands that don't seem built for juggling.”

Today, Joy has found happiness and peace and has come full circle, perhaps. “I think the woods are one of the few places where my mind goes empty,” he says. “I treat that space like church.”