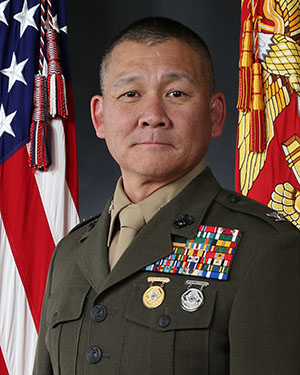

Once a Marine, Always a Marine

07 Sep 2021

Eric Terashima finds himself positively busy as a retiree

By TERESA McLAMB

Since retiring from the US Marine Corps on June 1, Eric Terashima has volunteered to be webmaster, Facebook manager and public affairs officer for both his American Legion and VFW posts. He was elected chairman of Brunswick County Democratic Party and serves on the board of directors of Habitat for Humanity. “It’s really fulfilling,” says Terashima. “So far, I’m almost busier in retirement. Talking to all the retirees out here, that seems to be a common affliction.”

He also has two part-time jobs. As an adjunct professor for Command and Staff College at Camp LeJeune, he instructs young majors and senior captains in strategic planning. Terashima signed on with Onebrief to do combined joint task force staff training over Zoom once a month. “I’ve got twenty plus years of staff work under my belt. I and a bunch of other field grade officers across the country are working on this exercise,” says Terashima.

Born in Los Angeles, Terashima moved with his family when he was three to a new construction neighborhood in Fountain Valley, California. His father was a Japanese immigrant. His mother was the third generation of her Japanese family to be born as a US citizen.

As the neighborhood grew, so did Terashima’s circle of friends and schoolmates. “We played outside; baseball, football, and did all the normal things like Cub Scouts and Little League Baseball. I got into martial arts when I was older and swam competitively for ten years,” recalls Terashima. In high school he competed in wrestling. He captained the water polo team and swim team and was an officer in the Key Club and French Club. “I was the typical over achiever,” says Terashima. His French lessons came in handy with deployments working with the French Foreign Legion in Africa and living on the German/French border.

Following high school, Terashima contemplated entering the service, but was persuaded by his mother to go to college first and enlist later. Assisted by an ROTC full-ride scholarship, Terashima pursued his degree at Notre Dame. “I struggled a little bit at first. I went from big fish in a little sea 1A school of about 1,000 people to Notre Dame with brilliant geniuses,” Terashima says.

His roommate, also in ROTC, invited him to the shooting team. By junior year, Terashima was the captain. On the day before graduation, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant.

The irony is not lost on Terashima that he chose to serve the country that interred and deported his mother’s family during World War II despite the fact that they were all native-born citizens as had been three generations before them.

“I really had to contemplate, and what I found inspiring was the soldiers of 442nd Regimental Combat Team (American citizens of Japanese descent), Tuskegee Airmen and others who overcame the racism of their time and still served,”

“I really had to contemplate, and what I found inspiring was the soldiers of 442nd Regimental Combat Team (American citizens of Japanese descent), Tuskegee Airmen and others who overcame the racism of their time and still served,”

says Terashima.

Despite a bit of a rough start in the Marine Corps, Terashima found himself enjoying it. It was the 1990s when there was more training than combat. Stationed at Camp LeJeune, he spent time in Okinawa and Korea. “From a strategic standpoint, we were there as the ready forces in case something happened in East Asia,” Terashima says.

In 1997, Terashima left active duty, joined the reserves and started a career with John Deere, which moved him around North Carolina, Wisconsin, California and Nevada. “In five years, I did about six jobs and had four different reserve units,” Terashima says.

“Then 9/11 happened, and we got mobilized for the war,” recalls Terashima.

At the time, the Marine Corps renewed contracts annually. He kept renewing and deploying. His ex-wife suggested he go back full-time. “She would say that I was a horrible civilian,” Terashima recalls.

He agreed.

A few years later he met Eva. They married eleven years ago and moved to Wilmington. Commuting to Camp LeJeune, Terashima found himself sleeping on his office floor Monday through Friday. “It was wretched. Plus there were deployments,” Terashima says. They moved to Virginia while he was stationed there. “It was a miserable failure,” says Terashima. “Eva’s business suffered. She suffered.” They decided to move back to Brunswick County where Eva could concentrate on her Cotton Exchange business, Down to Earth Oils, and he could “play marine.”

He moved to New Orleans, then Germany. “Luckily, I got back to LeJeune the last four years. That worked out really well,” says Terashima. However, Terashima notes, that he felt he was too old to sleep on the floor. He bought a 54-foot 1973 Hatteras, moved it into the base marina, and stayed onboard Monday thru Friday until he retired. Terashima also comments that he was forced to retire by the military’s 30-year commission

service policy.

That does not, however, mean leaving behind his military life. Just 19 days after retirement, an emotional Terashima and one of his former Afghan interpreters, called MH for his privacy and safety, embraced at Dallas International Airport. MH, his wife and two young children were the first interpreter family successfully brought to the US to start a new life specifically through Terashima’s fundraising efforts. Terashima drove from Wilmington to Dallas to greet them.

Following their reunion, he drove to Chicago to pick up another new arrival and took him to Aurora, Colorado to begin the settling in process.

Estimates are that about 17,000 Afghans worked as interpreters for the US, living alongside our forces during the long years the US were in Afghanistan. These individuals and their families are likely all at risk for cooperating with the Americans, Terashima and others have repeated.

Though a special immigration program, the interpreters and their families can apply for visas to the US, but the process takes years. In addition to documentation, there are medical screenings, and then the cost of airplane tickets to the US. “The cost of the visa is $600 per person,” he says, “which is in excess of the median annual household income in Afghanistan.”

He recounts seeing a government plan to bring about 2,500 individuals to the US by the end of July or August. “The broader problem is that Afghanistan is not secure. You can get people out of Kabul, but not the outlying areas,” says Terashima. Many of the interpreters live in these remote areas of the country.

Many started working on the immigration application months ago. “Back in May, the first one contacted me and said he was going into the last step which is the medical screening,” says Terashima.

Knowing that money would be a huge problem for these families, Terashima promised to help. “I wired the money over so they could go to the medical screening. Then once they got the visas, I bought airplane tickets.” Donations have been made to a Go Fund Me page (https://gofund.me/ff68e134), but much of the expense has been paid by Terashima.

Contact has been primarily through social media due to the lack of electricity and unstable wi-fi in many areas.

The first family, MH’s family, arrived June 19. “I planned it so they left [Afghanistan] and arrived in the US on Juneteenth. He certainly appreciated the fact that I specifically chose Juneteenth to fly him and his family out. That made it more significant to me as well,” says Terashima.

Once here, there are nonprofit organizations that work with refugees in about a dozen cities including Dallas. “Because these nonprofits are already set up in these cities, that means my interpreter friends have a built in ex-pat network that’s already there. When I went to the airport to pick him up, an ex-pat associate was also there, and put him up in his apartment,” says Terashima.

The family is now in temporary housing supplied by a nonprofit, and MH’s wife is enrolled in an ESL class.

Since then, he has sent $6,000 to pay for medical screening for ten people. “I’m waiting on word they’ve gotten their visas,” says Terashima. “And, yes. I will absolutely go to meet them when they arrive.”