In the Field

10 Jul 2017

Meet our local leaders in law enforcement, as they share with us those moments that stand out in their careers

By JAMIE LYNN MILLER

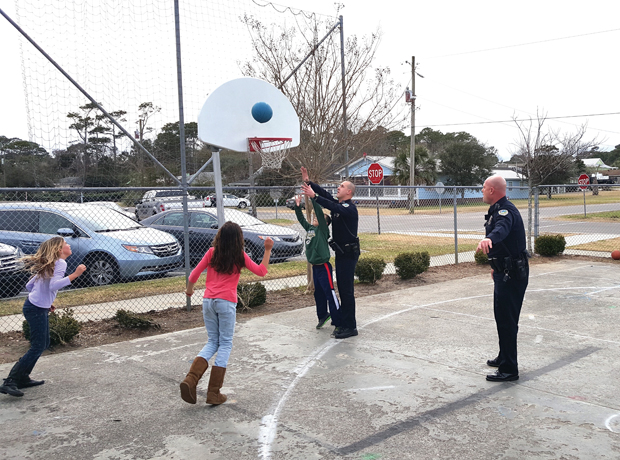

In the field, in the line of duty, out and about in restaurants, parks, and―you guessed it, Britt’s Donuts, police officers around the area interact with their communities. “Young kids think our job is to write tickets and put people in jail,” says Senior Detective Sonny Russell, of the Carolina Beach Police Department. “But really, I view our job as trying to help. When a bike chain comes off, or helping someone on crutches carry groceries upstairs … when we’re able to do a good deed, it shows the public we’re human too.”

With so many stories from the field, not all of them positive, the ones that really matter—the ones to pass on—are those that resonate with a sense of humanity. These are the stories for the grandkids.

Chief Mike James

“I have seven grandkids, actually,” says Chief Mike James of the Leland Police Department, over lunch at Paddy’s Hollow, one of his favorite Wilmington eateries. From Rockingham County to Brunswick County, and now, Leland, Chief James brings over three decades of expertise to the department, including training, education, and community outreach.

“I love teaching,” says James, who’s taught criminal justice at several community colleges. He also worked with 2nd graders through the Child Abuse Reduction Effort (C.A.R.E) program. “After my sessions with the kids, we had at least 2 or 3 kids come forth and report on abuse at home.” They knew that something was wrong, said James, and were able to speak up to the proper authorities. “It was a very rewarding effort,” he says. “And it gave the kids a chance to see the police in a different light, rather than ‘those people who come to the house and knock on the door.’”

Community outreach is key, says James. And when community reaches back? It’s a story worth telling.

“With 35 years of memories,” says James, “some things you don’t forget. Then you think about things you’ve forgotten.”

“This story started out sad, but it turned kind of happy. In 1986, I was working in Madison, North Carolina, and it was Christmas Eve. I got a call about a lady who was going through a dumpster, so I sent an officer out to investigate. Turns out, the woman had just lost her job, she had four or five kids, and her husband was in jail. She was going through the dumpster hoping to find something to give her kids for Christmas.”

“This was back in the days of scanners,” he adds, with a chuckle―“we didn’t have the fancy new equipment, so I put out a bulletin. We got about 30 calls from people who wanted to help…they went under their Christmas trees, into closets, and started dropping off presents. By about four in the morning, we’d gathered a whole pickup truck load of gifts and we drove to her house.”

“We were just going to drop them off, but the woman insisted on waking the kids up. They were all small kids, too, and they couldn’t believe their eyes. We just said ‘Santa’s running late, and he asked us to help him out.’”

He smiles. “You know, that story reminds me that people are still good at heart. Watch the news today, all we hear is the bad stuff. But most people just want to help.”

Detective Sonny Russell

Born and raised in Wilmington and on the force for 22 years—police officer, corporal, and now, Senior Detective—Detective Sonny Russell works with Chief Spivey of the Carolina Beach Police Department.

“Carolina Beach is a small enough community, where we should know the residents and they should know us,” says Russell.

“There are the heartaches and headaches, working the swing shift…we deal with hard and sometimes bad things,” he observes. “And then, something like this happens.”

“This story is actually from my first year of work, over 20 years ago. I was called to a domestic dispute. The man was a war veteran in his late 50’s, early 60’s, and he was in a wheelchair. The couple’s apartment wasn’t set up for handicapped ease, so the man spent most of his time in the garage, or on the first level. It was a bad setup, and the couple was really struggling.”

“I had the time that day to really sit and listen, and ask some questions,” says Russell. “I called Veteran Affairs and Adult Social Services to put them in touch with some resources,” he recalls, of the efforts to mitigate the more aggravating factors of the situation.

“About a year later,” says Russell, “I read a story in the StarNews focusing on that particular couple. They’d fixed things in their home life, had sold their house and were now living in a single story dwelling, where he could easily maneuver around. Veteran Affairs had helped them; they were happier and seemed to have worked things out.”

“At the end of the day, whether it was me or someone else who helped, they were able to stay together and live a happier life. They were able to find the help they needed.”

Assistant Chief Jim Varrone

“I went from a poor college student in New York, to a poor public servant trying to put his daughter through college,” says Wilmington’s Assistant Chief Jim Varrone, with a chuckle.

Unfortunately, after 30 years on the force, a lot of the memories are negative. “My job is to ensure that people have the resources to do their job,” says Varrone. “We deal with aggravated assault and property crimes, human trafficking, gangs, illegal narcotics—and traffic,” he adds, with a weary smile. “There’s no one silver bullet that will solve things.”

Varrone recalls a particularly disheartening moment involving drugs, the fight for life; and ultimately, death. “An officer saved a 35-year-old man’s life with Narcan, a powerful reversing substance,” he explains. Within 24 hours, the man had gotten a hold of more drugs and ended up OD’ing in a motel room.” He shakes his head.

“But there are some good things too,” he says. “To make it a full career and keep it positive, you need to find a positive connection to the community,” says Varrone, easing toward a tale of a happier, more fulfilling day on the job.

“Before moving to NC, I worked in a group home for mentally-handicapped adults,” he shares. “I was a peak aide for about a year, because I wanted to help those people; I felt it was a part of our community that gets neglected.”

“I learned a lot about myself, and about being grateful,” he shares. “The adults I worked with were so grateful for every little thing in their lives, you know?”

Fast forward 31 years to a couple of weeks ago, when Varrone participated in the Law Enforcement Special Olympics Torchlight Run. “It’s a 12-mile run from Castle Hayne to Wrightsville Beach, and about 25 to 30 officers ran it.”

“It was one of the better days I’ve had in a long time,” he says, “and it brought back memories of my job in that group home. The people we run for? They live year-round for that event. To see their smiles, feel their joy at seeing all those people coming out to raise awareness…It was a good feeling.”

“I might go a whole week and it feels like I didn’t accomplish a thing,” says Varrone, of the largely uphill nature of his day-to-day police work. “But for me, that day, I really felt like I made a difference.”