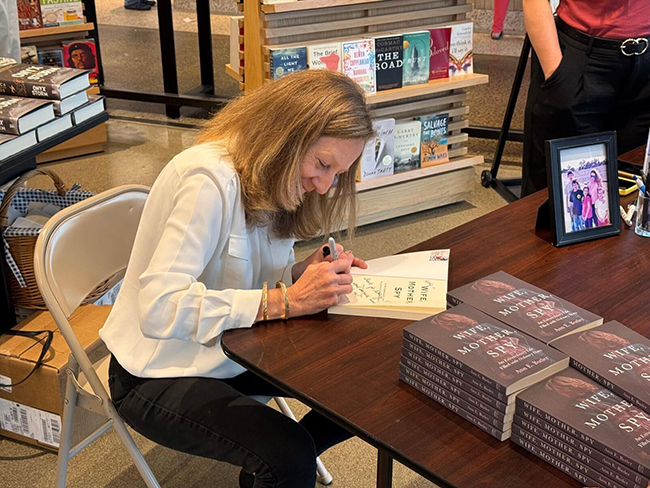

Preparing Now for a Bloom-Filled Spring

03 Jan 2026

A winter gardening guide for coastal North Carolina

By Natasha Walker

The trees are bare, the lawns are faded, and garden beds look sleepy at best. But don’t let the cold, moody temporary landscape stop you from preparing for a burst of color and life in March and April. Now is one of the most important times of year for gardeners to set that stage. Here’s a quick guide to the plants that benefit most from winter attention—and how to prepare your garden for a vibrant spring.

Planting spring-flowering bulbs

Winter is the final window to get bulbs in the ground since they need time to root in cool soil, and many require a certain number of “chill hours” to bloom properly. Daffodils, hyacinths, crocuses, and alliums all perform beautifully in our coastal climate and can be planted into early winter if the soil is still workable.

Tulips, a favorite for their bold colors and elegant shape, are the exception. Because Wilmington’s winters are relatively warm—minus last year’s unusual snow days—tulips rarely get enough cold exposure to rebloom naturally year after year. For best results, gardeners often pre-chill tulip bulbs in the refrigerator for 10–12 weeks before planting. Even so, most treat tulips as annuals, enjoying one spectacular spring before replacing them the following season.

Regardless of the type, bulbs appreciate loose, well-drained soil and a sunny spot. Add a bit of bone meal when you plant; then, cover with two to three inches of mulch to regulate soil temperature through fluctuating winter weather.

Cool-season annuals

Winter is prime time for planting hardy annuals—often called “cool flowers”—that thrive in chilly weather and burst into bloom much earlier than warm-season varieties. These plants establish roots during winter and reward you with lush, abundant spring growth.

Snapdragons, sweet peas, dianthus, bachelor's buttons, larkspur, and poppies all perform remarkably well in our coastal USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 8, characterized by mild winters (10-20°F minimums) and long growing seasons. Many of these annuals can survive light frost, and some—especially sweet peas and poppies—require the cold to germinate properly.

Dividing and replanting perennials

While many perennials go dormant in winter, this pause in growth makes it an ideal time to divide or transplant them. Division revitalizes mature plants, prevents overcrowding, and encourages healthier blooms in spring.

Perennials like daylilies, irises, hostas, Shasta daisies, and phlox all benefit from winter attention. If clumps look congested or if flowering diminished last year, dividing them is a smart move. Replant divisions promptly, keeping the soil evenly moist until roots take hold.

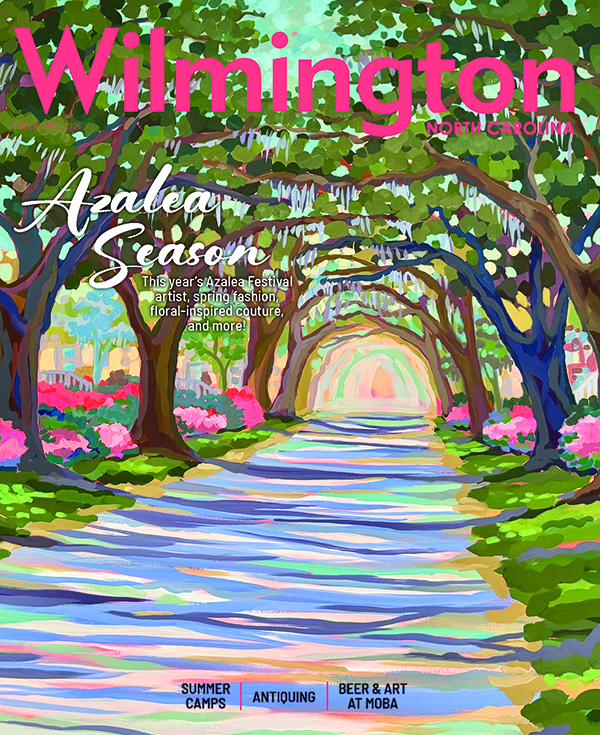

Flowering shrubs that set buds in winter

Several of the South’s most iconic spring-blooming shrubs spend winter quietly forming buds. Proper care during these months ensures abundant flowering later. Camellias, azaleas, forsythia, pieris japonica, and various viburnum species all begin setting buds well before spring arrives.

Along the North Carolina coast, camellias shine particularly bright. Sasanqua varieties bloom from fall into winter, while japonicas open their ruffled flowers from late winter into early spring, often before anything else in the garden wakes up. Protect them from harsh winter winds and avoid pruning them until after they bloom; cutting now may remove this year’s buds.

Azaleas, an obvious local favorite, also need time to develop their spring buds. A layer of mulch around their base helps retain soil moisture and protects shallow roots from temperature swings.Biennials and native wildflowers

Biennial favorites such as foxglove, hollyhock, and sweet William follow a two-year life cycle, forming foliage the first year and blooming the next. Planting or transplanting them in late fall or winter ensures they develop strong root systems and receive the cold period required for blooming.

Winter is also a natural time to sow many native wildflowers. Plants like black-eyed Susan, milkweed, coreopsis, and purple coneflower depend on cold stratification—exposure to winter moisture and freeze–thaw cycles—to germinate. Simply scatter seeds over prepared soil, press them gently into the surface, and let nature handle the rest.

It may look dreary now, but fortunately for us, spring in the South often arrives early and generously. A few thoughtful steps now can transform your garden into a welcoming burst of color by the time azaleas and dogwoods signal the season’s arrival.