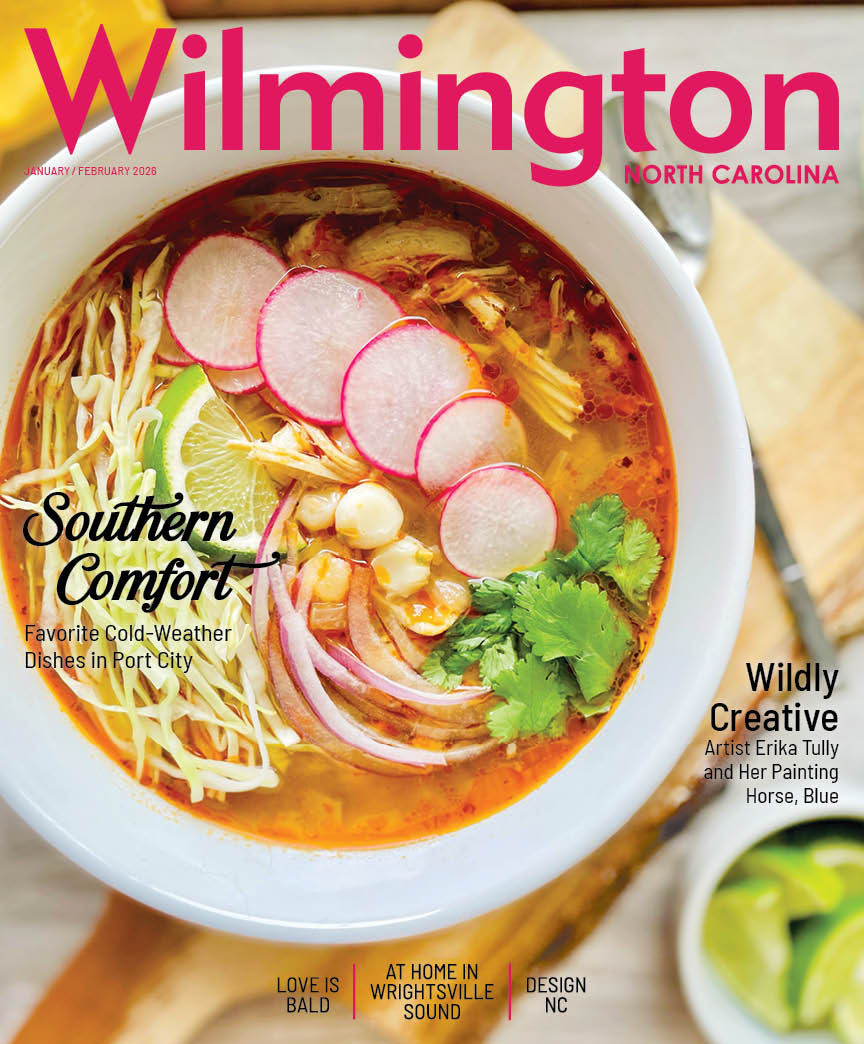

Rain Gardens as a Natural Solution to Flooding and Pollution

04 Nov 2025

Rain Gardens as a Natural Solution to Flooding and Pollution

With heavy rainfall and sandy soils, Wilmington is uniquely suited to benefit from these living water filters

By Madison Bailey

Imagine a heavy summer downpour. Rain hits your roof, flows through gutters, and rushes down the driveway into the street. Along the way, it picks up fertilizer, car oil, pet waste, sediment and other pollutants from lawns, roads and driveways before spilling into nearby creeks and marshes. The result: contaminated water.

How could something so natural, so essential to all life, become a problem? The truth is, it’s not the rain that’s changed—it’s us. Over the last century, we’ve paved forests, drained wetlands and covered the ground with rooftops and roads. Rainfall that once naturally seeped into the soil now races across hard surfaces, picking up pollutants, fueling floods and leaving less water to replenish the ground beneath us.

Now imagine that same storm, but your downspout directs water into a shallow basin filled with plants—a rain garden. Instead of rushing away, the water slows. Soil enriched with sand, compost and native topsoil absorbs and filters it, leaving creeks and marshes cleaner and healthier.

What is a rain garden?

A rain garden is a shallow, planted depression designed to capture stormwater runoff long enough for it to soak into the ground instead of rushing away. Filled with deep-rooted native plants and healthy soils, these gardens act like natural sponges by slowing water, filtering pollutants and helping replenish groundwater.

A well-designed rain garden is dry most of the time, holding water only for a day or two after storms. To neighbors, it looks like a flower bed full of color and movement. For the environment, it does the heavy lifting of stormwater management—work we often assume only giant pipes and treatment plants can handle.

Why rain gardens matter for Wilmington

Every storm that rolls through Wilmington is a reminder of our relationship with water. For too long, we’ve treated rain as something to rush away, a nuisance to be piped out of sight. But really, our landscapes just need to be ready to receive it.

The best part about rain gardens is that they tackle multiple challenges at once. They help reduce flooding by releasing stormwater slowly, which can prevent localized water buildup—a crucial benefit for Wilmington, which averages 60 inches of rain each year, among the highest totals in major U.S. cities.

According to Anna Reh-Gingerich, watershed coordinator for City of Wilmington Stormwater, even a small storm can take a toll. “It only takes an inch and a half of rain to wash most pollution off of impervious surfaces,” she said. “In general, our area has a lot of sandy or well-draining soils. So it makes it a really prime opportunity to be able to put in rain gardens.”

Wilmington’s cost-share program supports these efforts. Commercial properties, HOAs and mixed-use developments can receive rebates of up to $20,000 for installing green infrastructure, including rain gardens.

Rain gardens also improve water quality by filtering pollutants before they reach rivers and marshes, protecting the Cape Fear River—a vital source of drinking water—and supporting the health of plants, animals and communities that depend on it.

In a place like Wilmington, where many enjoy kayaking, swimming and eating local shellfish, rain gardens are especially important. According to Reh-Gingerich, many oyster beds in the area are closed due to high bacteria levels, which stormwater runoff consistently contributes. By preventing this pollution from reaching creeks, rain gardens help safeguard both recreation and food sources.

How to start your rain garden

You don’t need to be a stormwater engineer to make a difference. Rain gardens are accessible projects for anyone, and they can start small. Look at where your gutters or driveway drain—could you redirect a downspout into a garden bed? Even a residential rain garden can absorb thousands of gallons of water each year.

Ideally, a rain garden should sit between the source of runoff and where the water would otherwise flow, intercepting it before it reaches storm drains, streams or low-lying areas. Avoid spots that stay soggy long after it rains.

Plant choice is key. Switchgrass, black-eyed Susans, Joe Pye weed and river oats—all native to Wilmington—stabilize soil, soak up moisture and filter pollutants. “You want to try to plant it with native plants so that you don’t need extra fertilizers or pesticides,” Reh-Gingerich said. “They’re already acclimated to the area and used to the conditions. Once it’s established, it really functions like a regular garden.”

And while one rain garden might not change the world, a hundred can change a neighborhood. A thousand can change a city. Imagine Wilmington dotted with rain gardens—from backyards to schoolyards to public parks—all working quietly with every storm to keep rivers clean, streets dry and communities thriving. Rain is coming, as it always has. The question is: What path will we give it?